Timing. Isn’t that what life’s all about? If you’re there at the right moment, it all works out. If you’re there late, you’re at someone else’s fate. If you’re there too early, all that effort might not be for naught. If you’re speaking about Japan’s Kusu Kusu (and their album, 世界が一番幸せな日 (Sekai Ga Ichiban Shiawase Na Nichi) or “The Happiest Day In the World”), perhaps, now is their time.

Kusu Kusu made their first appearance to the world in 1988 at the Shimokitazawa Attic club. A four-piece group, consisting of Jiro Kawakami on vocals, Say on bass, Mu on guitar, and Makoto Miyata on drums, must have appeared like aliens descending on another planet.

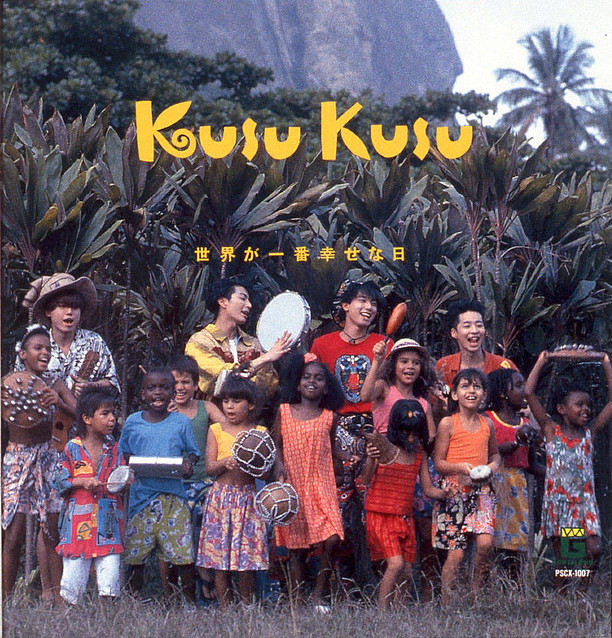

Unlike other groups burgeoning from the area who were tuned into the sounds punk, ska, and hardcore, here were a few country boys from Hokkaido playing music that seemed inspired by West Africa and the Caribbean. At that moment, unlike the other groups found in other hip locales like Shibuya and Shinjuku, their sound was not centered on reigniting the flames of forgotten Exotica esoterica or a new European jetset sound. Donning onstage African-print harem pants and a mishmash of urban streetwear were the foursome, playing longform songs that aimed to make you dance with joy, rather than scream and shout.

Perhaps, Shimokitazawa was the perfect place to make their debut. It was its more relaxed, bohemian vibe that allowed younger groups like theirs to explore more cosmopolitan ideas that other parts of the larger metropolis might gloss over or ignore. Originally, it was Jiro and Mu who made the trip from Hokkaido to Tokyo to explore African music they had enjoyed listening to as teenagers. They were able to convince the others, Say and Makoto, to start a band and practice together as “Kusu Kusu” (a play on the English word cous-cous and the japanese word for “grinning”) to do a deep dive into other global musical influences.

As an outgrowth of their local performances, they were invited to record for a compilation dubbed Panic Paradise featuring other groups bubbling from that scene like future dub-pop heavies, Fishmans. Appropriately so, it would be Kusu Kusu and Fishmans that would graduate in a way to bigger things. In Kusu Kusu’s case, it would be by growing more infamous through their lively live performances, drawing a young crowd drawn to their eccentric fashion and music. Appearances in local TV shows would then lead to a record deal with local indie label, Gorilland Records.

In 1989, Kusu Kusu would travel to Bali, Indonesia to perform their first concert outside of Japan, parlaying that experience into the studio ready to put forward a new sound to tape. 光の国の子供達 ((Hikari no Kuni no Kodomodachi) or “The Children of the Country of Light” was released to great critical acclaim. Featuring songs like “子供達へ” and “光の丘の木の下で” it showed a young group convincingly taking on certain musical strains of Nigerian highlife, Central African soukous and “Zulu” rock and reimagining these styles for their Japanese audience (rather than functioning as a cover band or watering the music down with reverence)…The Rhythm Of The Saints this would not be.

A brief hiatus, as members of the band graduated from high school – and a new opportunity: signing to a major label, Polydor’s Polystar, would lead to Kusu Kusu being afforded a stint to live in Brazil, where’d they’d stay in São Paulo imbibing of its atmosphere and absorbing the music of South America like samba, MPB, and candomblé . There they would transform what had been somewhat scattered ideas on their debut into a focused statement in the studio. By the time they flew over to the iconic Compass Point Studios in the Bahamas to finish the rest of the album, Kusu Kusu had fleshed out an album unlike little else on the Japanese archipelago.

世界が一番幸せな日 (Sekai Ga Ichiban Shiawase Na Nichi) aims for the bleachers. Songs like “ナンマラケッチィデヤ” take the call and response of Africa and fuse it with their distinctly homespun maximalism. It’s no surprise that just a year later, Kusu Kusu would take this songs to the storied Budokan and sellout across Japan. The songs on 1990’s 世界が一番幸せな日 (Sekai Ga Ichiban Shiawase Na Nichi) had this anthemic, catch-all personality to them that could be all things to all people, even if the grooves were decidedly of a certain space.

What makes me single out this album to the rest that would come later from Kusu Kusu is because of myriad hat-wearing and accessorizing they could do to their sound. Songs like “花咲華人” would not have existed if they hadn’t absorbed the radio sounds of the Caribbean. “あんべや” goes deeper into little niches of African music, yet doesn’t lose their youthful exuberance to play with the Japanese word and ease it into their musical vocabulary. Unsurprisingly, they’d make appearances in Jamaican festivals and not skip a beat.

The asides that pump the brakes on 世界が一番幸せな日 (Sekai Ga Ichiban Shiawase Na Nichi), like “ぼくとボク”, reveal the folksy, melodic underpinning never far off on their best work. It may sound corny to say this, but Kusu Kusu was this lively, vibrant flash in the Japanese pan when they exuded that youthful, naivety of the world. Technically, they were gifted musicians – evidenced by their single “世界が一番幸せな日” – who didn’t retreat from attempting styles they hadn’t fully explored but the lack of pretense helped fuel appearances, experiences, and performances that felt moving with movement. Songs like “ヘッドヒカラセ” and “鉄の森” speak to their ability to shift through many moods using one multi-varied pulse.

Dance music, for all intents and purposes, Kusu Kusu showed (at least in Japan) wasn’t only the provenance of those indebted to electronic grooves. Weirdly enough, perhaps it’s in that near past, when groups like Adam and the Ants or The Talking Heads were prowling the earth, that Kusu Kusu would have felt a better kinship to speak to: “that’s what we’re trying to do”.

Yet, for all the brilliance of that brief period they recorded and performed to wide popularity, somehow, their music seems little spoken of elsewhere (unlike the recent revival of similar brethren, Fishmans). When they broke up in 1994, their critical presence, seemingly, vanished with the times. Hopefully, this time around we can provide more grace to what they accomplished then.