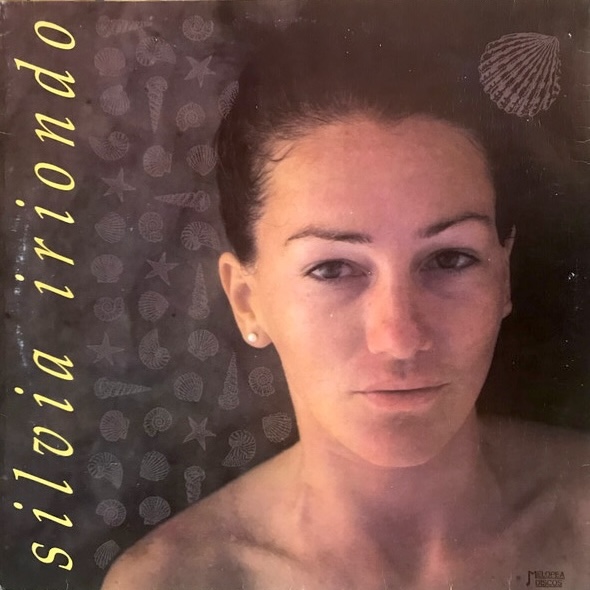

Few artists have done quite as much to advance the idea of a “nuevo canción” quite like Argentina’s Silvia Iriondo. Yet, perhaps, her most impressive work, 1990’s Silvia Iriondo remains quite a mystery. In it you hear Silvia – with help from Argentina’s experimental fusion and jazz scene – give voice to the little-admired music of the campo, music of the gaucho troubadour, and (most importantly) of the Afro-Peruano, in such a way that can speak to changing history of her country. In the end it’s their fusion on that album, that in hindsight, one can understand to put it at the vanguard of a new way to express a story.

Early on in Silvia’s background one can sense the push and pull of the past and modernity. Although born and raised in Buenos Aires, Argentina, from a young age, Silvia felt empathy and a certain connection to the more rural parts of the country.

Whether on the radio or hearing songs in the air, it was the songs of the iconic Chilean singer-songwriter, Violeta Parra or of those of “La Negra”, Mercedes Sosa, that gave her a glimpse of the feminine language one can use to understand quotidian life. From Mexico, Silvia was impressed by the writings and art of Frida Kahlo and drawn to her little-known theater works. Out of step with her peers, rather than listen to rock and pop, Silvia would find an affinity with the music of Argentinian neighbors like Brazil and Uruguay.

By the time, Silvia was old enough to explore a musical career, Silvia was of an age to understand that her vision would involve finding a way to express a folkloric language. In the beginning, Silvia’s early records in the early ‘70s on RCA appeared tentative and more feal to her inspirations. Whether from lack of success or simply from having to move on, in the late ‘80s, Silvia resolved to look elsewhere and find her own voice in the milieu.

It was during this lost period that Silvia developed an affinity for more rhythmic music, began to explore more “aboriginal” styles, and expanded her musical taste to include more contemporary ideas. By late ‘80s, opportunities would open for Silvia to perform for Secretaría de Cultura de la Municipalidad de Buenos Aires and to self-release musical projects that were entirely written by her. At the crossroads of going back to the past and exploring the future, Silvia took a run forward. Silvia signed with Argentinian indie label Melopea Records.

There’s one thing one can’t accuse Silvia’s new label of being: backwards-looking. Melopea was founded in 1979 by Litto Nebia on the ashes of his career. Inspired by the Nueva Trova music of Cuba’s Silvio Rodríguez and Pablo Milanés, the outré-ethno Brazilian music of Egberto Gismonti, and the genre-fluid jazz experimentation of fellow countryman, Astor Piazzolla, Litto felt compelled to create a label where like-minded Latin American artists could transform the sound of their homeland.

In the beginning, Melopea served as a testing ground for Litto’s own fascinating musical experiments. In due time, solo acts like: Gonzalo Rubalcaba, Urbano Moraes, Mariana Ingold, or groups like Alfombra Magica or Grupo Taxy and Mate Luna, would build up its roster with impressive genre-spanning work that still sounds remarkably forward-thinking.

It’s in this hot-bed of South American experimentation that artists would collaborate and perform on each other’s records, creating ideas that took more personal inspiration. It’s in this cross-pollinating environment that Silvia was dropped into to reimagine her idea of what folk music could be.

From July to October, 1989 in Estudio Films Records, in Buenos Aires, demos of her music to were deconstructed and reconstructed by keyboardist, Carlos “El Negro” Aguirre. Production was left entirely in the hands of Silvia herself. A core group of musicians – bassists Jorge Cerrato and Matías González from Alfombra Mágica, Porta Alegre’s tango guitarist Osvaldo Burucuá, and drummer, Marcelo García – would flesh out the music, giving it it’s impressive slipperiness.

In the Argentine capital, others like Gustavo Mozzi, Daniel Curto, Luis Barbiero, Pablo Blasberg, Marcela Passadore, Moli Verón and more, artists that would help cultivate and shape what would be Argentina’s new alternative rock scene would lend a hand when they could. What would become of Silvia Iriondo would be an album that posits all these sprawling wheels of sounds into a spoke – one that spoke to a more immediate audience.

You hear it in Silvia’s reimagining of Maria Elena Walsh’s gorgeous Argentine protest gem, “La Paciencia Pobrecita” into an even more haunting feminist tome. Alberto Muñoz’s “Angel De La Mañana” transforms into a floating quasi-ambient jazz ballad, befitting its lyricism. Deep cuts of new Argentinian folk-adjacent music, like Gustavo Santaolalla’s “El Cardon” take orbital views of the tradition they’re rooted in. Others like “Se Me Olvidó Que Te Olvide” find Silvia exploring that bridge between jazz and milonga. On one of the album’s highlights, “Isla Mujeres”, a pointillistic original weaves a mix of disparate grooves, atmospheres, and emotions, winding through truly “new folkloric” music just as windy and bracing as the waterways it’s inspired by.

On the flip, another original song, Silvia’s “Canción De Arena” finds us caught in another haunting minimalist electro-acoustic ballad, one inspired by the windswept sands of the Argentine seaside. Sonically brave and unlike little else, it elongates and pulls the essence of Argentine balladry in new directions with every word Silvia sings. It’s that spirits that all those involved help transmit into Silvia’s reimagining of one of those totemic songs of the Argentinian folk tradition: Jaime Davalos’s “El Jangadero”. On this, Silvia’s self-titled debut, this classic rekindles with the embers of its flame transmuted through Mercedes Sosa, picking up a new, floating quality that’s positively beautiful – something far more befitting the lingering, wandering spirit of the original.

The album would wind down with two Silvia Iriondo originals. One, “Traigo Flores En Mi Canasta”, would point in the direction Silvia would head in the future, finding ways to express the deep Argentinian folk tradition in a way driven by the grooves of jazz. The other, “Compañero Del Aire”, solidifies that spacious inviting journey one can take when putting on this record. Here we’re lucky to experience Silvia trapezing her voice through all sorts of lovelorn musical beatitudes and attitudes, landing on this wonderful love song.

What I found deeply appreciative and impressed about Silvia Iriondo is how she bookends the album with “Las Hojas Tienen Mudanza”. Originally written by multi-hyphenate singer-songwriter, musicologist, poet, and much more, Leda Valladares (the other half of the Leda and Maria duo), Silvia takes a song truly indebted to the more humble music of Argentina’s Bolivian border and imbues it with a renewed sense of inspiration and magnitude – just like it did long ago for one of her inspirations. Although her mind expresses a new set of tools and an evolved sense of lyrical vocabulary and musical language, her soul (as heard in this track) remains ever tied to the spirit of this ever restless soul music. And when the spirit moves, it sure moves in mysterious ways.