Stand By Satie? It’s pretty hard not to, when a whole slew of musicians – in all styles and genres – have been inspired by the late, great French impressionist composer. But how does one take the next step and actually attempt to interpret the man? It’s a question, I imagine, that was cycling in Toshiro Mitsutomi’s head when he chose to give Satie a different spin.

Toshiro’s journey to Erik Satie’s music in a roundabout way. A native of Shibuya, born in post-WWII Tokyo,Toshiro wouldn’t pick up his choice of instrument – the flute – until he was in middle school. It was originally the jazz music of Herbie Mann and other jazz cats that spurred him to take on composition, theory, and other music education.

It was in Tokyo’s Aoyama Gakuin University where he’d translate his love of writing and the French language (another of his passions) into a more rigorous focus – a study of French literature. At that moment both musical composition and writing were competing pursuits. By the mid ‘70s, Toshiro got wind that if he wanted to pursue a career in music his best bet would be to pursue his education in America.

Blessed are the persons who venture to one Carbondale, Illinois (in the middle of nowhere) and graduate from the University Of Southern Illinois, as Toshiro would. Because it was there, In the heart of the American midwest, Toshiro would take his diploma to Michigan and earn his masters at Michigan State University. Thankfully, it was in Lansing he would then be able to study under the tutelage of France’s preeminent flutist, Marcel Moyse. There, for a period of time, he was the lead flutist for the Lansing symphony orchestra.

When Toshiro would return to Japan in the mid ‘80s, he discovered a Japanese society in the throes of an economic and cultural boom. What was once a waning home record industry now held endless possibilities (and opportunities) for seasoned musicians just like him.

Toshiro would quickly engross himself as a session musician working in a diversity of styles, with a diverse clientele like Akira Sakata, Yoko Kanno, and Haruna Miyake (to name a few) that span the gamut of free jazz, experimental, and classical music. Pushing himself to work without regard to genre, Toshiro recalls working with Yann Tomita and Seiko Ito on their groundbreaking 1986 Japanese rap album, 建設的 and who he’d revisit on their gorgeous rework of “Country Living” off their Subliminal Calm release. However, it would be just two years later in 1988, when Toshiro finally received his first opportunity to create or, better yet, recreate a different kind of subliminal calm for the first work bearing his name on it.

At that moment in time, Toshiro had grown cognizant and knowledgeable of a distinct Japanese musical style that was bubbling up dubbed “healing music”. When Toshiba EMI signed him to their Who Ring label, they probably realized he didn’t fit its contemporary fusion-focused roster. Perhaps that’s why his placement in their AGF series made sense. What Toshiro wanted to explore musically was closer to what fellow label mate, Keishi Urata was thinking of. It’s to get closer to that idea of Japanese interior music – where music can paint a picture that is missing in someone’s world.

Unsurprising, in hindsight, what this “fragrant music” – as AGF described such music – meant for Toshiro would be to contemporize a long-time influence: the “furniture music” of Erik Satie in a more interior way. Doing so would allow Toshiro to use modern instruments like drum machines, samplers, synths, alongside the acoustic instruments of the orchestrated past, like his flute.

For two weeks in mid May, 1988, Toshiro took up residence at Tokyo’s famed Onkio Haus studios and reimagined Satie for a younger generation. Satie’s “cold cuts”, his Pièces Froides, appeared as bite-sized ambient motifs. Variations of the bubbly Sports et Divertissements took on a technodelic swing, similar to Satsuki Shibano’s reimagining of Pascal Comelade’s canon. Toshiro’s take on the Gnossiennes put up front his wonderful flute phrasing with little experimental touches via atmospheric edges. And everyone’s favorite, Gymnopedie no.1, makes its breathtaking appearance in a heavenly arranged floating interpretation (where Toshiro’s flute playing goes for it).

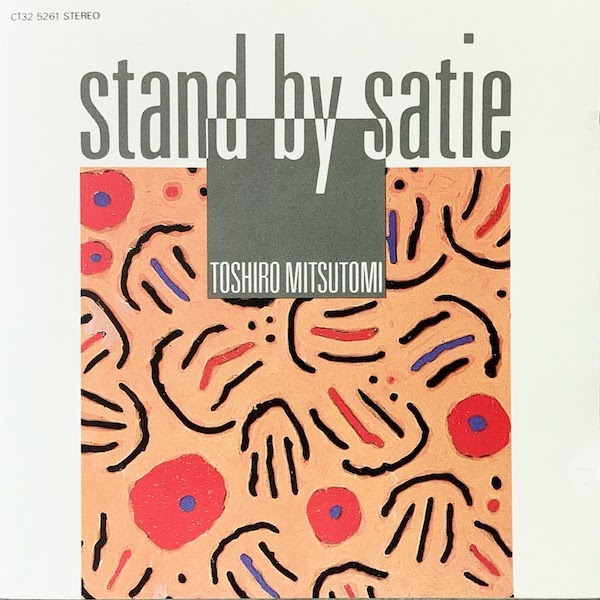

Although my copy of this album lacks the wonderful booklet that comes with a complete original copy (c’est la vie), I can only imagine the kind of artwork chosen to accompany this release. Surely, Toshiro’s take on the original “incidental music” – that of Satie’s Le Fils des Étoiles – deserved a canvas full of marigold, maroon, and azure, to match his more atmospheric take. Surely, the sweet ending to Stand By Satie, Toshiro’s sprightly Je Te Veux merits some space in our modern world. It’s that bit of something for everyone – a classic reimagined with some fantastic original ideas, by someone who really taps into a certain mood (closer to the original’s spirit).