With Valentine’s Day upon us, I thought I’d share an album that’s one of those perfect mood makers. I’ve often said this: “I love love songs.” Most of my most treasured albums, songs, and mixes hover around that whole idea, “What is love?” And in today’s case, in Yoshiro Nakamura’s Literário it’s when does our love for something actually blossom and take off, becoming something else. For those that have a long and deep affection for Brazilian-influenced music, Literário remains a perfect introduction to just how that influence can be reimagined and reinterpreted by newcomers who dig a little deeper in their own way.

If you know anything about Yoshiro Nakamura, it’s that he’s the closest Japan has come to its own João Gilberto. Whether at your local Japanese library or on TV or on the radio, most likely, you’ve encountered Yoshiro doing something – perhaps performing or presenting his latest book – something that is promoting his longtime love of Brazilian music. Some of those most widely heard interpretations of the works of bossa nova giants like Tom Jobim, Vinícius de Moraes, Luiz Bonfá, and more, are those reimagined by Yoshiro. As much as one can sense a deep affection for Brazil’s music in Yoshiro, this love wasn’t one that came to him instantly.

Born and raised in Osaka, in 1952, part of Japan’s baby boom generation, Yoshiro readily admits that from a young age he didn’t really appreciate music. The first time Yoshiro heard jazz or experienced the music he’d come to, it struck him as the music of the rich and elite (something his humble upbringing couldn’t connect with). Bossa nova music, as he experienced it in his early years, as performed by Stan Getz and on CTI Records, was the glossy, American thing played at cocktail places.

What changed Yoshiro’s mind was a bit of fortune. While attending Kyoto’s Doshisha University pursuing a career in engineering, he happened upon a performance by Baden Powell on campus. Hearing songs spanning Baden’s career, from Os Afro Sambas to Apaixonado, led him to discover that certain feeling, that of saudade that had eluded him in western interpretations. It was in Baden’s music he could hear how you could “sing or speak with your guitar”.

By the time the Baden’s concert was over, Yoshiro was so overcome, he felt a kinship to this music. So much so, he felt compelled to make it his goal to travel to the place where it came from. So, after graduating, Yoshiro took up a certain “backpacker” spirit. In 1977, Yoshiro took his rucksack and a guitar, and set his sights for Central and South America.

When Yoshiro ventured into Brazil’s capital, São Paulo, that’s where he discovered that this music he had fallen for ultimately had roots in more humble beginnings. Whether being performed communally, among friends, or trafficked in bars, on a street corner, or by the beach, everywhere this music was performed, it was never too far from performers who learned it…not in some conservatory or playing it to the bourgeoisie…but by those who picked it up when someone shared a few chords or bars. The mystery of the music was there for Yoshiro to unravel, if he dedicated himself to learning.

Yoshiro’s early goal was to make it to Rio. It was in Rio De Janeiro where, seemingly, anyone who’s anyone was seen performing on its stages and recording in its high-end studios. If he could find someone to teach him the way of bossa nova it had to be there.

Unfortunately, for Yoshiro he’d only get as far as Bahia. It was somewhere in Brazil’s Nordeste, that on some fateful day, Yoshiro’s wallet was stolen. Penniless, without identification or a passport, nearly 2000 kilometers from his destination, Yoshiro was – for all intents and purposes – unhoused and relying on the kindness and generosity of others. Unbeknown to Yoshiro, he was the closest he’d ever been to the heart and soul of this music.

It would be in Salvador, Bahia, that Yoshiro was fortunate to encounter people who provided him a place to stay and afforded him a chance to continue his journey. During his stay there, Yoshiro was able to discover the literal connection this land had to the music of João Gilberto and Vinicius de Moraes. The influence of Afro and indigenous Brazilians left a special mark on him. The language, which he was forced to pick up and practice, became a part of him. All that new history Yoshiro was learning would push him further into newer territory, uncovering musical ideas that he could never shake off.

When Yoshiro came back to Japan, in 1980, he made it a point to see if he could introduce that music to Japanese audiences. In the beginning, Yoshiro’s biggest struggle was finding Japanese people who could understand what he was trying to do. As a guitarist, he’d find himself often performing in sessions for fusion groups like Hidefumi Toki’s Samba Friends or Naoya Matsuoka’s Wesing. Although the opportunities were great, the music he was making felt increasingly like that sterile, impersonal music he hated as a young listener. In that era of Japanese excess, there was no place for the kind of more personal, ruminative, Brazilian-influenced music he wanted to create.

Thankfully, things would change for Yoshiro. It all began in 1988 with his introduction into the group, Acoustic Club. It was there that he’d befriend younger musicians, musicians like Hiroki Miyano, Rie Akagi, and Toshihiro Nakanishi, who had that similar drive to go deeper into their influences and actually create new music (rather than a pastiche of the past). On songs like “L’Agrimas De La Araucana” from Aquascape you could hear a more organic, mercurial sound that felt closer to myriad influences he heard in Bahia. So, it would come as no surprise that when Yoshiro looked to create his first solo album, he’d invite its members to be an integral part of its sessions.

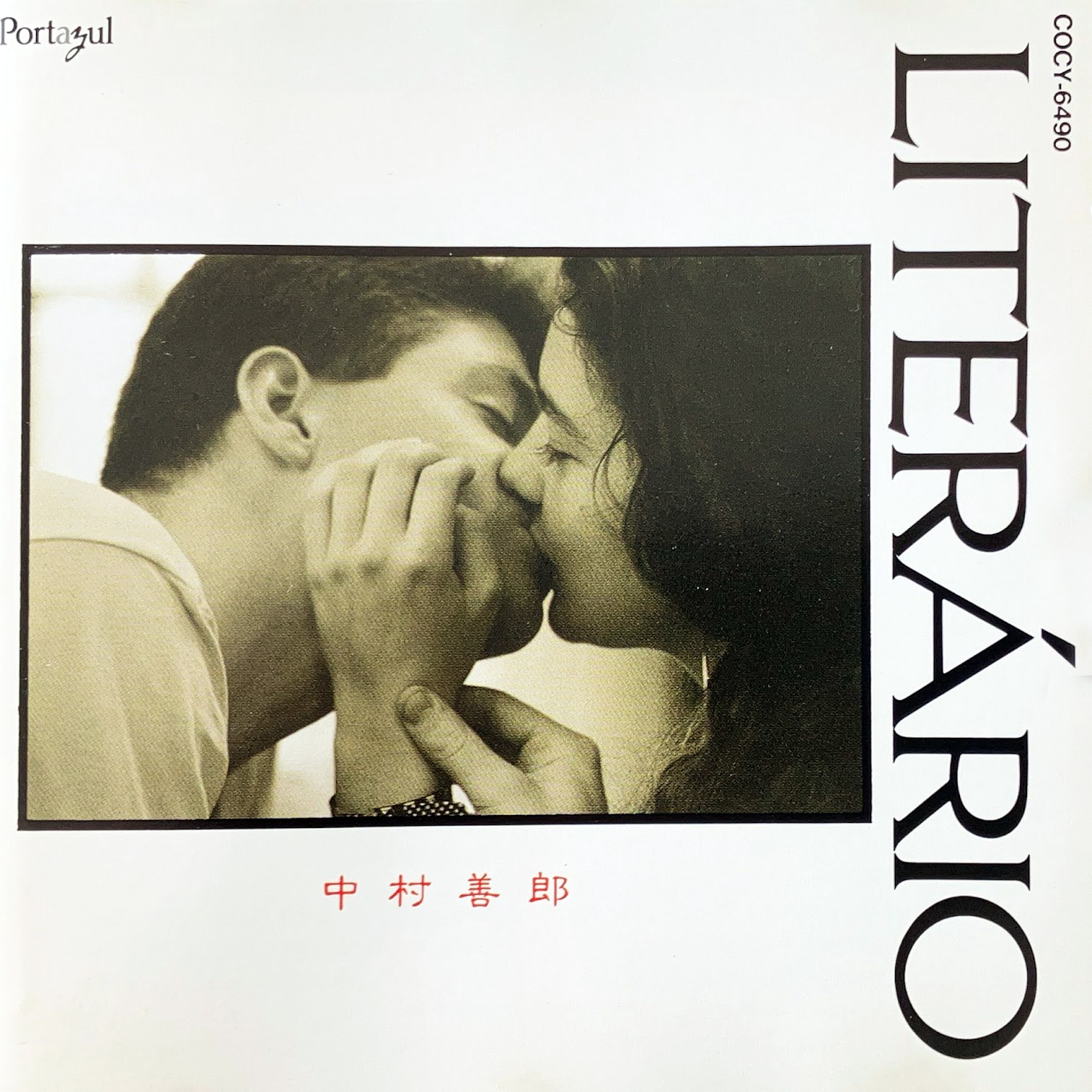

In 1990, Yoshiro would finally get that opportunity to put his name on the front cover by Japanese record label, Portazul. Looking to cash in on a new Japanese boom in the interest in bossa nova music, one kickstarted by Lisa Ono and Pierre Barouh, Nippon Columbia started Portazul as an offshoot to release more “tropical”-minded music made by those at home and abroad. Thankfully, Yoshiro found a home to express the kind Brazilian music he’d always wanted to create.

For two months – from March to April, 1990 – Yoshiro and friends were given time at Columbia’s iconic Tokyo studios to tape a warm distillation of a certain lost Brazilian style. Songs like the opener, a cover of Baden Powell’s “a. Samba De Bénção – b.Seu Olhar <a.祝福のサンバ・b.君のまなざし>” pointed to the totem guiding their steps. Suave, sophisticated, and quite intimate, on the next track, on the equally gorgeous Yoshiro original, “Então <それから>”, leverages the esoteric piano stylings of Fond/Sound favorite, Febian Reza Pane, to create something at a level the old “masters” would have beamed to have written.

That wonderful delicate touch of leaning into saudade, of understanding how sculpt nostalgic sounds, guides “Tempo Feliz <幸せのとき>”, molding a longing ballad into something quite spectral and intimate. Everywhere you hear Yoshiro’s graceful voice and zen-like guitar penning music that’s transportive to a different time. “Me Manda O Seu Retrato <君の写真を送っておくれ>” is that ditty that lightens the tone with a deft samba that makes perfect use of Ichiko Hashimoto’s guest talents, questing that cocktail jazz heard in more, once again, intimate settings.

Literário was titled that way because Yoshiro wanted to capture the “literary” quality found in a good love story. The best kinds were ironic tales where love speaks itself from a different angle. On the first of two instrumentals, “Setembro Azul #1 <青い九月No.1>”, we get to experience it by hearing Yoshiro’s guitar having a conversation with Kazutoki Umezu’s sax. Full of unequal push-and-pulls, only the introduction of Febian’s piano resolves a tender motif they’re trying to land on. It’s a gorgeous touch on an album that can segue through all sorts of stylistic movements.

Sonia Rosa’s wonderful guest spot on “Cafezinho <コーヒー・ブレイク>” put us closer to the Bahia-based sound Yoshiro fell for. The of João Gilberto-isms of “Um Pobre Rapaz <あなたを想うだけ>” makes one wonder just how someone like Yoshiro was able to capture that beatific spirit of melodicism found in his influence. At any point others would have taken this song elsewhere, perhaps losing the importance of nuance, yet, Yoshiro yin’s where other yang, yang. It’s those little spiritual touches that stick with you on second and third listening. You keep thinking, this was an original thought not lost to the past.

It’s ideas heard on “Um Caminho Que Eu Andei <私の歩いた道>”, “Adius Boa Viajem <さよなら、ボン・ボワヤージュ>” and “Dorme Menina <おやすみt>” that speak to the talent of an artist that build that bridge to an era where simple things could be profound. The magic of course is how the music of Literário, like any good book, like any good cup of wine, like any good company, simply gets better with age, revealing certain notes the longer they linger in your memory. And in my fair opinion, it’s Yoshiro Nakamura’s debut that has that perfect vintage with long legs that sticks with you (long after its gone).

Reply