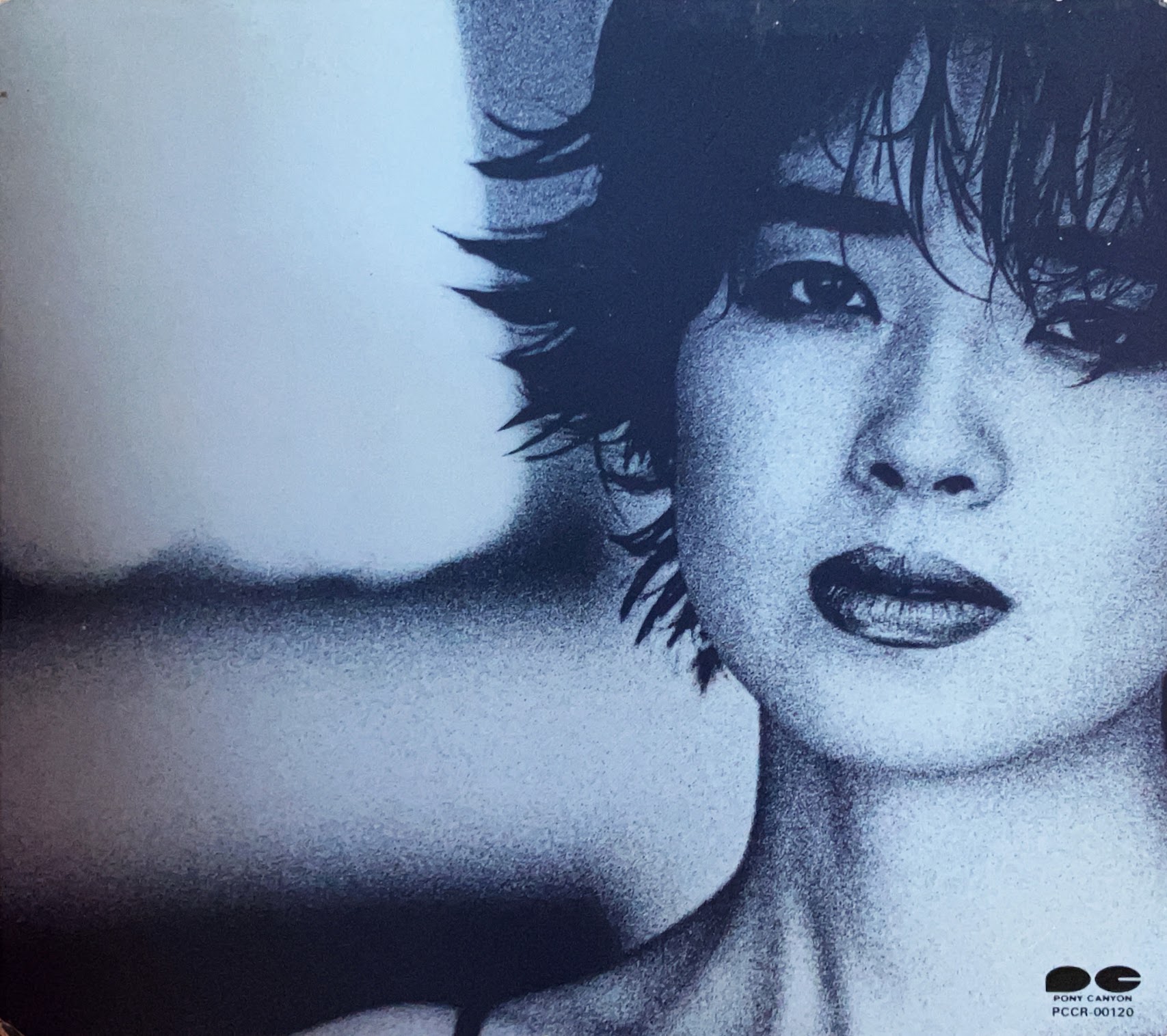

It’s not often you recognize “genius” straight away, yet it’s not often you get to hear such precocious brilliance of the likes seen in Yukiyo Nakamura. From her debut in 1989 to her latest work, what could have turned out as a different kind of musician, blossomed into their own kind by finding her true north. Although the focus of our north star is her The Arch Of The Heavens, I can’t recommend enough checking out her other work (if you can run into it somewhere).

Yukiyo was born in the Japanese seaside town of Kamakura, just south of Tokyo. Her earliest musical experiences came courtesy of her family’s home organ. Back then, in the early ‘70s, it was Yamaha’s first attempt to introduce a swiss army-style electronic organ – one that can play all sorts of different tones by engaging different switches – that allowed it to create something they’d dub the “Electone” (the same organ Yukiyo created and experimented with her first fantasias at the age of 9). Before Nord’s Electro electrified many a stage with their iconic red visage, here was this large monstrosity delivering equally extensive user-selectable tones and rhythmic accompaniments.

It was Yamaha, by the early ‘80s, this massive multi-industry company, who conceived huge international music tournaments to show off the technical prowess of their most-current instruments by pitting the world’s best self-described “Electonists” against each other, in a compositional battle-royale. If ever you’ve trolled through Discog’s search filter, there you can uncover countless records by many winners of said long-running tournament. Unfortunately, “winning” often meant charting a course towards the safe lands of Easy Listening, adding to Japan’s unending stream of BGM.

So, you can imagine the crossroads that entering said contest presented to Yuki. At the age of 20, Yukiyo would enter the 1987 edition of Yamaha’s Electone Concours Grand Prix and win its top prize. Shortly thereafter, Yukiyo would sign to Fuji’s Pony Canyon record label (seemingly) to enter the pop market. Thankfully, she had different plans.

Working on her debut with her wonderfully understated producer, Masahiko Satoh, Yukiyo was given freedom to compose all her material and to work with equally simpatico musicians like The AB’s Fujimaru Yoshino and Atsuo Okamoto. Together, they’d run the gamut, from styles like jazz, ambient, New Age to “ethnic” music and Neoclassical motifs, exploring ideas that were far from easy listening. When they turned in her self-titled debut record, one could imagine what kind of surprise the label received. This was “deep easy listening” in the vein of Yukie Nishimura, Yuriko Nakamura, and others, more inline with more mature jazz artists, but not what they had imagined for her.

There are songs on 1989’s Yukiyo, like “Rather Innocent”, “Mahali Pazuri I” and “Windflower”, that point forward to influences perhaps in the world of Lyle Mays or predict explorations in the world of healing music and soundtrack she’d go through later. However, just a year later, on her sophomore release, 目の前のにんじん, it appeared that she had taken a sideways step and create something that’s partly hers and part at her label’s request. Hovering between the funky influence of New Jack Swing and smooth/fusion jazz, this release featured her first vocal-led songs but also showed mere glimpses of her unique musical talent between all the pleasing…but sadly, milquetoast…jamming.

Two years later, Yukiyo returned to form on 1992’s quite brilliant, Birthday. This time around she’d take the reins as co-producer, building a smaller team of session musicians to pare back her sound. Far more sophisticated in tone and ideas, Birthday leaned toward a more “acoustic” sound and was of the lineage of music heard on the ECM label. Surprisingly modal and mysterious, tracks like the opener, “慈雨”, or “Thinking Of You” and “The End Of The Day” unfurled in meditative, longing ways (coupling new depth in feeling with length in track time). Others like “Africa” and “炎 (…For The Love Of Your Life)” showed off Yukiyo’s sprawling, dialed-in, compositional and improvisational skills by touching on world music in a way that suited her newfound, mature sound.

By the time of 1994’s The Arch Of The Heavens, Yukiyo had become a successful composer and arranger for stage, film, and television. That ability to craft instant magic had begun to seep into her own work. What made this record stand apart was just the grander scope she looked to tackle with grandeur ideas (done in, perhaps, her most stately, personal way).

Seemingly inspired by Pat Metheny and Lyle Mays’s As Falls Wichita, So Falls Wichita Falls or the midnight jazz of Bill Evans, on songs like “Grace Of Blue” and opener “誘惑” (temptation) the weightless, elegant music focused more on atmosphere and texture than whiplash melodicism. For once, the haunting sounds of Yukiyo could conjure out of her original, chosen instrument, and sounded positively unlike anything else. Backed by the awfully elegant playing of her session musicians, they all hung back, meditating on bittersweet compositions that touched on Yukiyo’s melodic mindful rumination.

Tracks like “はるかな空の下で” (under the distand sky) belong to the neoclassical school of moody adventurism – combining field recording with contemporary orchestration. Others like “7月2日” (July 2nd.) dip waist deep into the world of environmental music, offering that Yukiyo (yes) could in fact explore these ideas. And The Arch Of The Heavens gets more impressive, simply by building its own world where Yukiyo’s ambitious ideas keep completely coming through. It’s no wonder she felt compelled to completely produce this album herself.

Going higher, on “雨” (rain), magnific, ambient jazz captures all the gradients of deep blue, Yukiyo felt necessary to convey. As the track times get even larger, approaching “post-rock” levels, each second is an earned length where this (once again) grand atmosphere is further explored to gorgeous results. The nearly six-minute, quite sexy and moody, length of “On The Borderline” allows Yukiyo to create perfect starlight healing music of a different kind. The nearly eight-minute long title track has every bit of that moving, adult sophistication befitting its melancholic, New Age sophistication, that allowed Yukiyo to build her own beautiful piano staircase to “Avalon”.

The Arch Of The Heavens ends with Yukiyo at her purest, writing an orchestrated 10-minute composition dubbed “The Last Frontier” a beautiful, haunting “classical” that revolves around a heart-breaking leitmotif. Which makes it even grander when Yukiyo kicks it into high-gear, stretching its contours out, coming in, showing you just where the borderline of her musical vision could extend. Now, where exactly was the horizon of this enigmatic masterpiece?

Perhaps, that clue can be found right above you (and somewhere below).