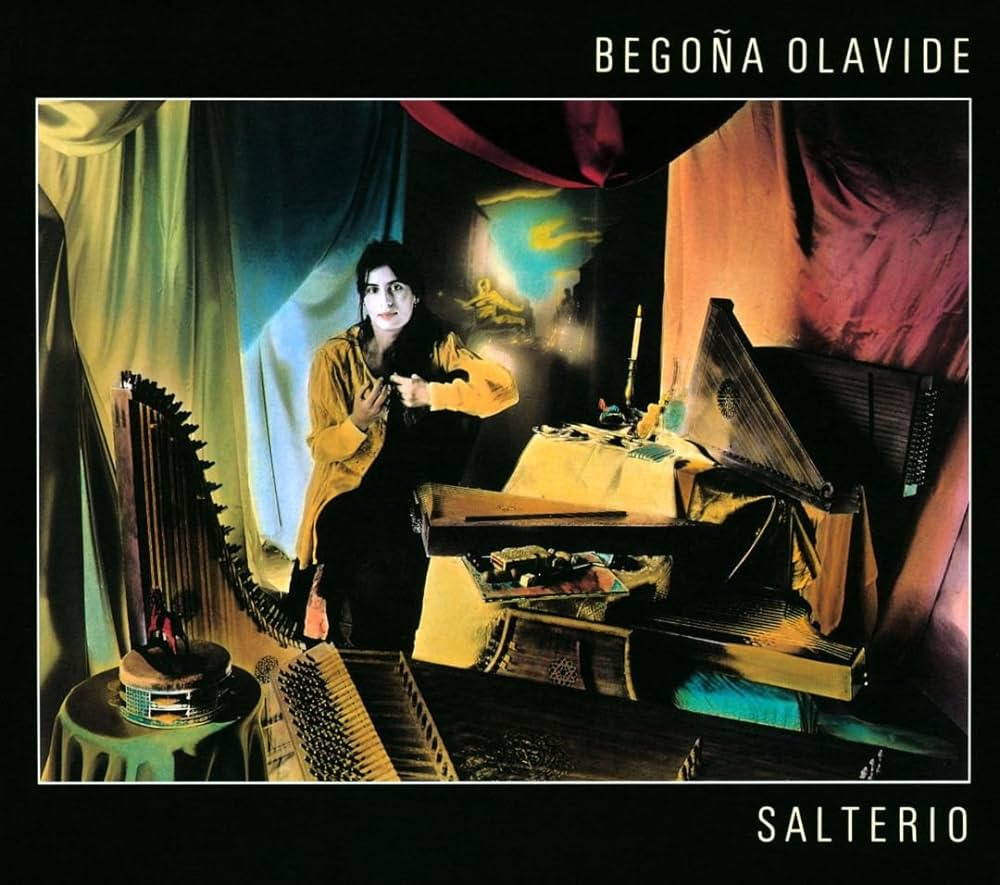

Is it: “Everything new is old again?” or is it: “Everything old is new again?” Before I left for my visit to Japan, I was freshly reminded of this paradox by (friend of the blog) Chris Morris’s YouTube share of an autumnal neo-folkloric favorite of mine: Begoña Olavide’s Salterio – one I reminded myself to expand on, on my return. It is within Salterio’s mix of the nearly forgotten past and the possible intimacy of an uncertain future you get a near pitch-perfect picture of just what you can achieve by sneaking a peek backward.

Salterio began as a germ of a thought in the mind of one Andalusian musician, Begoña Olavide. From a young age she was fascinated by the traditional music of the region. All that “early music” derived from the Maghreb and from Spain’s medieval period, played a role in spurring Begoña to involve herself in the study of this music and also to participate in various groups – both in theater and musical performance – that were responsible for exploring and reintroducing long, forgotten works to contemporary audiences. By the 1980’s an early proficiency and mastery of the flute was set aside for an exploration of psaltery and mastery of flamenco dance.

It was in the early ‘80s when Begoña would meet and fall in love with Madrileño musician, Carlos Paniagua. This connection would spring forth a fascinating new direction. As a founding member of Atrium Musicae De Madrid, Carlos (alongside the rest of the Paniagua brothers – Carlos, Eduardo, Eugenio, Gregorio and Luis) spearheaded a modern revival of ancient European chamber and folk music. As an ensemble, they were responsible for planting the seed for future groups like Finis Africae and others under the Grabaciones Accidentales that would try to search through all the many rungs of musical history that sustained the cultural story of Spain.

With time, though, together with Carlos Paniagua, Begoña would conceive and start the group, Cálamus. Leveraging Carlos’s technical skills as a luthier, they were able to study millennia-old songs and use historical ideas to fashion instruments that, seemingly, had been extinct and resurrect Andalusian songs that showed even deeper ties to Spain’s “Moorish” past and to largely, forgotten, female-played compositions. Other members like Luis Delgado and Rosa Olavide would introduce a cornucopia of instrumentation that expanded on what could have been a reverential take on the past, into one specially-tied to new possibilities.

It’s those new possibilities that would lead Carlos and Begoña to befriend one Todd Garfinkle. Todd was an itinerant American-born pianist composer who had made a name for himself in Japan performing piano duets with J-Jazz giant, Sadao Watanabe. Caught up in the heyday of Japan’s bubble economy, Todd was swept up by Sony to release an album of “easy listening” and just as easily left to wither on the vine with no plans for a follow up.

So, rather than give up his newfound life in Japan, Todd would start a new record label MA Recordings (deriving its name from the Japanese concept for space: “ma”) in 1988 to prioritize high-fidelity recordings using specially-designed omnidirectional microphones that put listeners right in the spatial thick of all sorts of new forms of “ethnic music” (with audio-quality rivaled by little-else out there), all that was recorded entirely outside of a studio, in venues that held a special acoustic imprint of their own.

Under MA Recordings, Begoña was given the latitude to dial-in exactly how close she could get to the original sound the age-old compositions required. Thankfully, for us, her partner and luthier, Carlos Paniagua understood the liberties he had to take to recreate the psaltery, the string instruments she’d had to master to capture a new spirit in those old songs.

Whether building “square” or “triangular” psaltery, the lack of technical history, the existence of only images (in some cases) for a majority of these instruments, forced the duo to take liberties with just how they could express themselves through these tools. History, of this sort, wasn’t clear-cut and the music, of this sort, allowed the performer to impart their own interpretation. Knowingly, they realized that whoever taught anyone how to play these resurrected instruments was long gone, and Begoña had to play the instruments to hear what they could teach her.

Recorded in the span of three days in March, 1994, at the monastery of Santa Espina in Valladolid, Spain using the latest in digital audio tape memory, old memories of long but not forgotten music, seemingly, wafted into existence through the fingers of Begoña. On Salterio you’d hear Nubian songs that survived only through the spoken word, assert their importance, as on opener, “Noche Maravillosa” (a song fully-fleshed out by her Calamus backing band). Museum pieces like “Lamento” from 14th century manuscripts of Tristan and Iseult receive that mystical, longing air inspired by Begoña’s and Carlos’s psaltery duet.

If you have access to the original liner notes, as I do, you can pour over the wonderful history of gorgeous songs like “La China”. You can go back to this song’s historical ties to the world of Sufism and the greater Andalusi music of Begoña’s antecedents. Devotional songs like “Laudemus y Explendens” and “Imperairitz” shimmer as that form of dance music they were originally meant to express.

Original expressions like Begona’s “Improvisacion” look toward the resurrected instrument for divined, divine inspiration just as so. Other songs like “Minuet” take the essence of its 18th century Madrileño multi-authorship and make it intimately hers. Salterio may not preserve everything as others intended but Begoña’s intentions and Carlos’s scholarship make this music, their music, intentionally, just as timeless.

Reply