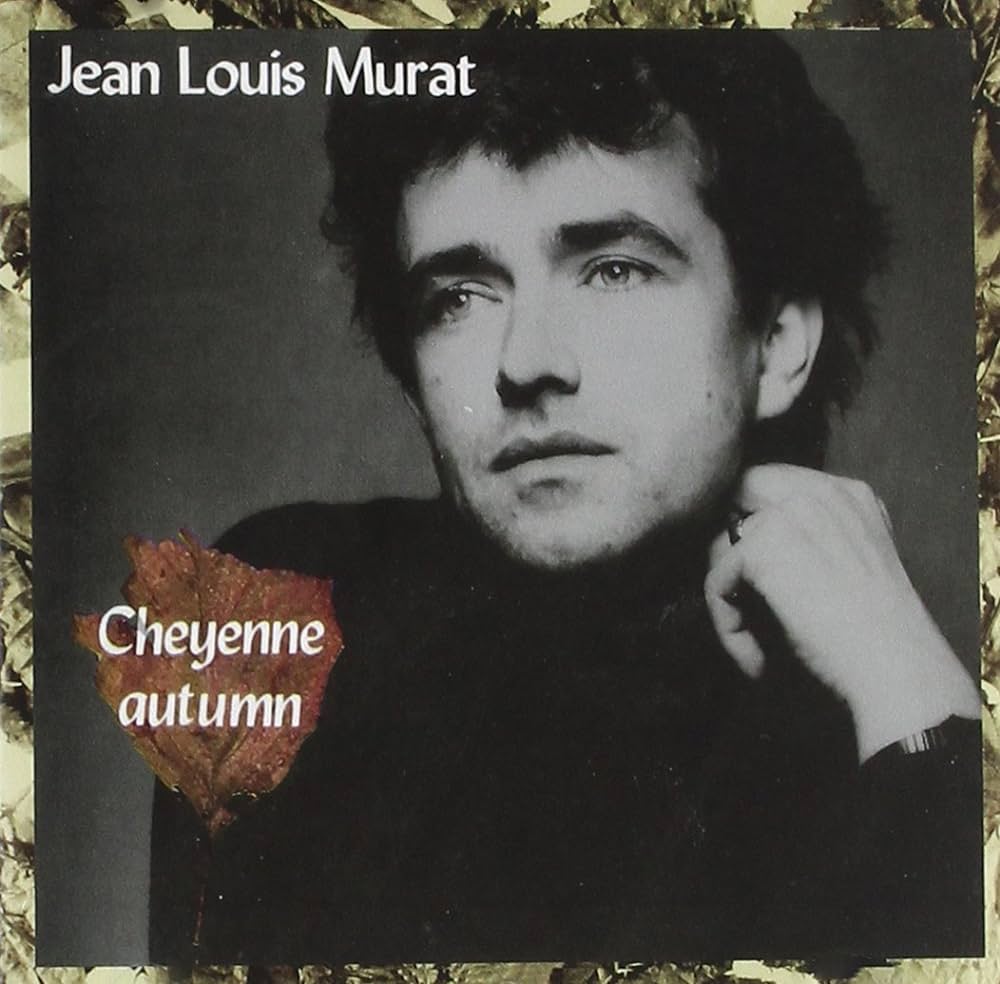

As the year begins to draw to a close, my mind goes back to some of the people we lost this year. I’m thinking of artist’s artists like Alan Rankine, Pharoah Sanders, Tina Turner, and YMO greats (like the sorely missed Ryuichi Sakamoto and Yukihiro Takahashi). In this year full of great loss, at the moment, though, my mind goes back to one death that largely flew under the radar: that of Jean-Louis Murat. It goes back to his masterpiece of “nouvelle chanson”, Cheyenne Autumn.

Revered among European music circles but largely little-known outside of his native France, Jean-Louis Murat’s work hovered in rarefied territory, where every new album and new experiment shifted the extent of just what one could do with the French ballad or pop song. Unflinchingly prolific, nearly every year, from his 1982 solo debut to 2021’s La Vraie Vie De Buck John, every year we were greeted with a release, reassuring us Jean-Louis was still probing for something new. Yet for all the critical accolades he’s amassed, the poetry of his music could simply be zeroed in by looking at a brief period at the end of the ‘80s.

Before he became this artistes’ artiste, there was a very shy, young singer in a rock-and-roll band, one Jean-Louis Bergheaud, trying to find his way around the music scene of his beloved Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes. Inspired more by nature, art, and poetry, than any of his contemporary music, Jean-Louis was left nearly directionless when his band, Clara, broke up. Of his musical influences, the unwavering visions by those like, Neil Young, Bob Dylan, and JJ Cale, inspired him to not quite give up his own.

Perhaps it was a mix of Jean-Louis’s piercing, crystal blue eyes or what was behind them, that would spur their manager to extend him an opportunity to give it a go as a solo singer-songwriter. So, in 1981, just 27 years old, Jean-Louis would adopt the stage name of Jean-Louis Murat (as a nod to the homeland of his ancestors in Murat-le-Quaire) and record a single, “Suicidez-vous Le Peuple Est Mort” featuring a cover photo shot by the iconic, Jean-Baptiste Mondino.

Whatever talent Jean-Louis had would slowly be swallowed by the outrage and conservative censorship machine. Pittance singles sales were made, as record shop owners were hard done to promote a record that had received nearly zero radio playback, due to its subject material. A year later, a mini album, Murat was released to nearly as many sales, unable to find a footing with its little-placeable mix of darker ambient jazz and pop fusion.

What started as a promising career (for an undoubtedly talented lyricist), nearly ended in 1984, as Jean-Louis Murat’s second album for EMI, Passions Privées, was released and sold just as many records as before. In spite of reaching a promising creative turning point, EMI dropped Jean-Louis and clipped his wings just as other musicians had begun to take notice of his unique forward-thinking sophisticated-kind of pop music. In 1985, full album recordings for CBS were shelved and Jean-Louis took the opportunity afforded to him by Richard Branson’s Virgin label to continue his career. They thought they were getting the next Julien Clerc but Jean-Louis had other ideas.

Kudos to Virgin for allowing Jean-Louis to take up to two years to come up with something that would signal a revival of his vision. It was in 1987, when Jean-Louis would reward their stewardship by presenting them with what would become his first hit single, “Si Je Devais Manquer De Toi”.

Predicting the nocturnal electro-pop balladry of musicians like Leonard Cohen and a furthering of the atmospheric tonal shift presented by Etienne Daho, “Si Je Devais Manquer De Toi” planted a new notch in the totem pole, raising a flag that finally caught notice of French culture at large.

Inspired by John Ford’s Westen-dispelling Western, Cheyenne Autumn, Jean-Louis took its decidedly unsexy themes of forced displacement (either emotional, physical, and environmental) and reworked them into expansive, elegiac songs and lyrics, rapidly fomenting in his music. Taking full reins of the album, he created songs like opener, “Les Animaux / Paradis Perdus” that spoke of rejecting perfumed gardens and sports cars for worn landscapes and lost paradises. Mixing atmospheric music with found sound and his elegant vocals and production, finally, Jean-Louis pointed clearly to an uncertain future.

Gorgeous songs like lead single, “L’Ange Déchu”, have this autumnal quality that speaks of the nostalgia in his music but also of the peril of dwelling too much in the past (for fear of the future). Cheyenne Autumn was this longing collection of mid-tempo music – all crimson, copper, and bronze – that piles up and piles up into a more powerful whole.

You hear this steady plasticine placidity in songs like the slightly uptempo Balearic number, “Amours Débutants”. Even seemingly simple songs like “Le Venin” have a certain Proustian kind of layer uniquely theirs. On the edges of Jean-Louis’s songs there was also something distinctly his, as in his reimagining of “Chega De Saudade” on “Pars”. Suave songs like “Le Garçon Qui Maudit Les Filles” harken less to any Gainsbourg-ian influence and more towards a Cohen-like spirit, circa Various Positions.

Arguably, the songs that stick with you are those uncategorizable vignettes like “Dejа Deux Siecles… 89…” songs that speak of true human suffering, that requires a different kind of rebellion. It’s something that builds to a trio of songs ending the album. “Pluie D’Automne” a meditation on seasonal longing, whisks you into floating ambient balladry that could be equal parts loving, nostalgic, but also fierce and solitary. Motifs gleaned from the failure of Manifest Destiny (or of trying to manifest destiny) color the silvery, horizon-filling, spectral country-lilting, “Le Troupeau”.

Then the album ends powerfully on the titular track, as bits and pieces of dialog from the film lace a pulsating ambient elegy to what? Love? To “nostalgia”, as the looped-voice of Andréi Tarkovsky intones? Or is it something speaking to the impertinence of the human experience? Whatever it was, the album spoke to a wide swath of forward-thinking French listeners who, finally, found a modest place for Murat’s music in their library.

Just a year or so later, Jean-Louis Murat would receive a letter in the mail from one Mylène Farmer, confiding in him his love for the album and a wish to sing a duet with him. She saw in his music a fraternal twin. What came of their collaboration, a love song, “Regrets”, would function as a parallel continuation to what started in Laurie Anderson’s and Peter Gabriel’s “This Is The Picture (Flying Birds)” – a successful culture-storming single that solidified the importance of their talents to a French-speaking world who missed part of the bigger picture. And later that year, in 1991, Jean-Louis would release a profound masterstroke capturing the terroir of his Auvergne — a painterly musician to the end.

So, in this season of remembrance, it’s high time (I think) we spare a thought for one of those, sadly gone but not forgotten.

2 responses

Thank you for your post, Diego. I think “Pars” is more based on “E Preciso Perdoar” than “Chega de Saudade”. I’ve always had a soft spot for “Cheyenne Autumn” but, in France, it’s more its next album, “Le Manteau de Pluie”, which is considered as his masterpiece.

You are correct! I stand corrected. Great choice for a song to reimagine.